Not all scars are created equal, and if you’ve ever wondered why some skin injuries fade away while others leave a lasting impression, you’re not alone. Atrophic scars, in particular, are often misunderstood. These indented marks, common after acne, surgery, or trauma — are more than just cosmetic concerns; they reflect a deeper story about how the skin heals and, sometimes, how it doesn’t.

In aesthetic practice, especially in Singapore where skin health is deeply linked to lifestyle, climate, and even cultural expectations, understanding the nuances of atrophic scarring is crucial. It’s not simply about surface-level treatments. It’s about decoding why the body sometimes “under-delivers” in its healing response — and how that response can be improved.

This article unpacks what atrophic scars are, why they form, and how the skin’s healing process varies across individuals and conditions. Whether you’re a practitioner aiming to better educate your patients, or someone navigating scar treatment options, this guide will offer science-backed clarity and a grounded view of real-world treatment possibilities.

What Are Scars?

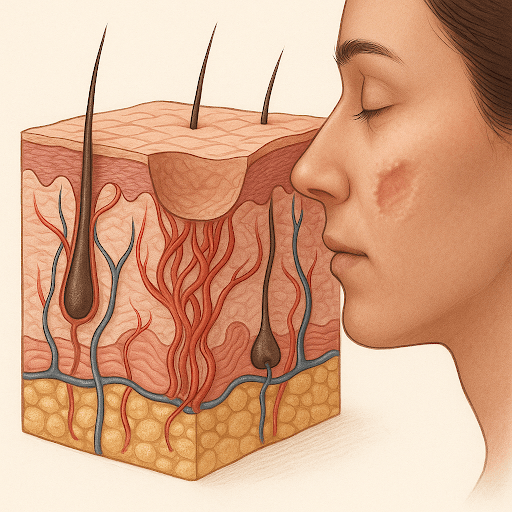

Scars are the body’s natural way of healing and replacing lost or damaged skin. They form when the dermis — the thick layer of skin beneath the surface — is injured. To repair the damage, the body rapidly produces collagen fibres to close the wound. The result? A scar.

But here’s the catch: this process is rushed and imperfect.

Unlike normal skin, scar tissue lacks hair follicles, sweat glands, and the orderly arrangement of collagen that gives skin its elasticity and smooth texture. That’s why scars can appear raised, flat, or indented — and why they often feel or behave differently than the surrounding skin.

Types of Scars

| Type of Scar | Appearance | Common Causes | Skin Texture |

| Hypertrophic | Raised, red or dark | Surgery, burns | Thick, firm |

| Keloid | Overgrown beyond wound area | Ear piercings, cuts | Rubbery, raised |

| Contracture | Tight, shiny skin | Burns | Tightened, rigid |

| Atrophic | Sunken, pitted | Acne, chickenpox, trauma | Thin, indented |

Atrophic scars are unique in that they sink below the skin’s surface, giving a “pitted” or “depressed” appearance. This happens because the body produces too little collagen during the healing phase — a stark contrast to hypertrophic or keloid scars, where collagen is overproduced.

This subtle imbalance in collagen production is what sets atrophic scars apart — and makes them more challenging to treat effectively.

The Healing Process of Skin

To understand why some scars, particularly atrophic ones, form the way they do, we need to look at the four key phases of skin healing. This process is remarkably efficient, but also sensitive to disruption at any stage.

The Four Phases of Wound Healing:

- Haemostasis (Minutes to Hours)

The moment the skin is injured, blood vessels constrict and clotting begins to prevent further bleeding. A temporary matrix (mainly fibrin) forms to stabilise the area. - Inflammation (Hours to Days)

White blood cells flood the site to remove bacteria, dead cells, and debris. This phase is essential — but prolonged inflammation can lead to poor healing outcomes and scarring. - Proliferation (Days to Weeks)

New tissue forms. Fibroblasts produce collagen, and new blood vessels develop (angiogenesis). The wound starts to contract, and the foundation of scar tissue is laid. - Remodelling (Weeks to Months)

The newly formed collagen is realigned along tension lines to strengthen the tissue. Ideally, this leads to a smooth, barely noticeable scar. However, when collagen is insufficient or poorly organised, an atrophic scar may develop.

While this process is broadly consistent, individual differences, such as genetics, nutrition, inflammation levels, and even sun exposure, can dramatically affect the outcome. In the case of atrophic scars, something in the cascade of healing underperforms, usually in the proliferation or remodelling phase, where collagen synthesis and organisation are crucial.

We’ll explore that failure in more depth in the next section.

Why Atrophic Scars Form

Scars aren’t just about the injury, they’re about how your body responds to that injury. And when it comes to atrophic scars, the response is notably lacking.

Among the various scar types, atrophic scars are characterised by tissue loss, resulting in depressions on the skin. This occurs when the body doesn’t produce enough collagen during the healing process, particularly during the proliferation and remodelling phases we discussed earlier.

Instead of building a full scaffold of new tissue to replace what was lost, the body cuts corners. It patches the wound with a thinner layer of tissue that lacks volume and structure, resulting in a sunken appearance.

Why Does This Happen?

Here are some of the most common reasons why collagen production may fall short:

- Inflammation overload: Prolonged or excessive inflammation (e.g. in cystic acne) disrupts fibroblast activity, reducing collagen synthesis.

- Nutrient deficiencies: Vitamin C, zinc, and protein are essential for the production of collagen. A lack of these can compromise the healing process.

- Genetic predisposition: Some individuals naturally produce less collagen or have slower wound-healing responses.

- Infection or re-injury: If a wound is reopened, infected, or improperly cared for, the skin may struggle to complete the healing process efficiently.

Common Triggers (Acne, Injuries, Surgery)

Atrophic scars don’t appear out of nowhere — they follow some of the most common skin traumas, especially those involving chronic inflammation, delayed healing, or deeper skin damage. Let’s break down the primary culprits behind these indented scars.

1. Acne (Especially Cystic or Inflammatory Acne)

Acne is the most common cause of atrophic scarring, particularly among teens and young adults in Singapore, where climate and genetics often play a role in persistent breakouts. Here’s why acne leaves these types of scars:

- Deep inflammation: Cystic acne penetrates deep into the dermis, damaging collagen-rich layers.

- Popping or picking: Physical disruption can worsen the wound and interfere with healing.

- Chronic outbreaks: Repeated cycles of inflammation don’t give skin enough time to regenerate effectively.

Common acne-related atrophic scar types include:

| Scar Type | Description |

| Ice Pick | Deep, narrow scars that look like punctures |

| Boxcar | Broad, rectangular depressions |

| Rolling | Wave-like skin texture caused by tethered dermal bands |

2. Injuries (Cuts, Bites, Abrasions)

Not all wounds heal equally. Deeper injuries that affect the dermis, such as bike accidents, animal bites, or even harsh cosmetic treatments gone wrong, may lead to atrophic scarring, especially if:

- There was poor wound care

- The wound became infected

- Healing was delayed or incomplete

In many cases, even small injuries can scar if they’re deep enough and collagen production is insufficient.

3. Surgical Procedures

While most surgical scars tend to be linear and hypertrophic, certain procedures, particularly skin biopsies, mole removals, or cosmetic surgeries, can result in atrophic scars if:

- Sutures weren’t well-aligned

- Post-op care was inadequate

- The incision site experienced tension or trauma during healing

In aesthetic clinics, it’s critical to educate patients on proper aftercare post-procedure, not just to avoid infection, but to support optimal collagen regeneration.

Scarring isn’t just about what happened, it’s about how your body responded. And in the case of atrophic scars, that response was muted or incomplete. But does that mean these scars are permanent?

Let’s address that next.

Can Atrophic Scars Improve Over Time?

The short answer: Yes — but not always on their own.

Unlike pigmentation or surface texture issues that may fade with skin turnover, atrophic scars involve a structural deficit in the dermis. This means the tissue is physically missing or sunken, and the body typically doesn’t “fill in” that void over time without some form of stimulation.

However, improvement is still possible — especially when the right biological and clinical conditions are met.

Natural Improvements (What the Body Can Do)

In mild cases, the body may gradually remodel scar tissue over 12 to 24 months, especially in younger individuals with robust collagen production. Key factors that influence natural improvement include:

- Age – Younger skin heals and regenerates more efficiently.

- Nutrition – Diets rich in protein, vitamin C, and antioxidants support tissue repair.

- Sun Protection – UV exposure worsens scar appearance by breaking down collagen.

- Inflammation Control – Reducing chronic inflammation (e.g. through acne management) can prevent new scars and allow existing ones to settle.

That said, most moderate to severe atrophic scars need intervention to meaningfully improve.

Clinical Interventions (What Aesthetic Clinics Can Do)

Here’s a comparative table of popular in-clinic treatments that stimulate collagen production to reduce atrophic scarring:

| Treatment | Mechanism | Best For | Downtime |

| Fractional CO₂ Laser | Microscopic skin injury triggers collagen | Boxcar, rolling scars | 5–7 days |

| Microneedling (with/without RF) | Induces micro-trauma to remodel skin | Mild to moderate scars | 1–3 days |

| Subcision | Releases tethered scar tissue | Rolling scars | 3–5 days |

| Dermal Fillers | Temporarily lifts depressed areas | All atrophic types (temporary) | Minimal |

| TCA CROSS | Targets deep scars with chemical peel | Ice pick scars | Minimal to moderate |

Most effective treatment plans combine modalities based on scar type and severity. A patient with mixed scarring (ice pick + rolling) may undergo subcision + laser for optimal results.

“Scars are not just a cosmetic issue — they’re a physiological story written on the skin. Treating them means rewriting that story with intention and precision.”

— Dr. Justin Boey, Medical Director, Sozo Aesthetic Clinic

What Doesn’t Work

It’s worth mentioning: topical creams and home remedies rarely improve atrophic scars significantly. While they can help reduce pigmentation or improve hydration, they do little for volume loss without mechanical stimulation.

Atrophic scars may not completely disappear, but with the right guidance and a strategic, long-term plan, their visibility and texture can be significantly improved — often enough to restore both appearance and confidence.

Conclusion

Atrophic scars aren’t just about appearances; they’re the result of a complex interplay between biology, injury, and healing potential. While they often seem stubborn and unyielding, understanding why they form is the first step toward effective treatment.

We’ve seen that these scars reflect collagen loss, not excess. They’re rooted in the body’s attempt to heal quickly rather than perfectly, and common triggers like acne, injuries, and surgical wounds merely set the stage; the real outcome depends on how your skin responds in the weeks and months that follow.

The good news? With the right knowledge, timely interventions, and clinical support, atrophic scars don’t have to be permanent. Whether you’re a practitioner supporting patients through their scar journey or someone personally affected by scarring, the key is to shift focus from “scar removal” to scar rehabilitation, restoring structure, rebuilding confidence, and respecting the biology behind each mark.

More than skin deep: Teen Acne & why you should be approaching it from the Inside-Out